Tokenized Assets: The Basquiat of Digital Assets

Why representation, not code, changes the accounting story

Tokenized assets are traditional financial or real-world assets issued on a blockchain, wrapping an identifiable asset or right into a ledger-based form. They may represent fractional ownership, revenue rights, or claims on an off-chain underlying (such as real estate, equities, commodities, revenue streams, or access rights), but are not themselves cryptocurrencies or the network’s native economic engine.

The token is not the value. The underlying asset or right is. This distinction is everything.

A tokenized asset may appear in numerous forms as outlined below:

Wrapped tokens: Blockchain representations of another asset (e.g., wrapped BTC or ETH). Their value depends on custodial or protocol integrity.

Governance tokens: Tokens that grant holders voting or decision-making rights over a blockchain protocol (e.g., rules, upgrades, treasury). Their value is speculative and tied to influence, not cash.

Synthetic tokens: Tokens that track the price of an underlying asset (e.g., stock, commodity, crypto) using collateral and algorithms. Holders gain exposure to price volatility and risk without owning the actual asset, and redemption is not guaranteed.

NFTs: These are tokenized claims on unique assets or rights (art, media, access, credentials). Liquidity is market driven not guaranteed and they are non-fungible by design; this simply means that unlike cryptocurrencies, each token is unique and cannot be swapped on a one-to-one basis.

Tokenized assets feel deceptively familiar to accountants, and then quickly become uncomfortable.

Tokenized Assets as Basquiat Paintings

Tokenized assets behave less like currency and more like a Basquiat. A Basquiat is unquestionably valuable. But its value doesn’t come from the canvas or paint. It comes from what the piece represents, who stands behind it, and how the market recognizes that claim. According to the New York Times, in 2017, a 1982 Basquiat sold for a whooping $110.5 Million at a Sotheby’s auction.

Two Basquiats are not interchangeable.

Ownership and provenance matters.

Rights, restrictions, and authenticity matter.

Tokenized assets work the same way.

The blockchain records ownership, transfer, and authenticity with mathematical precision. But the economic substance lives in contracts, custodial arrangements, legal enforceability, and in the relationship between the token and what it claims to represent.

This brings us to the real question finance teams must answer:

Are we accounting for a token, or for the thing the token points to?

And that’s where the classification tests begin.

1. Do Tokenized Assets Meet the Definition of Cash Equivalents?

Cash equivalents must be:

Stable in value

Short-term in nature, and

Readily convertible to known amounts of cash with insignificant risk of a change in value.

Tokenized assets almost always fail this test. At a glance, they feel closer to money than native tokens, for the very fact that they reference an underlying “something real” (i.e., real estate, equities and/or commodities). That alone tempts finance teams to reach for cash-like classification. But the problem is not what they reference. It’s how the token’s value is accessed, transferred, and enforced. Most tokenized assets introduce additional layers of variability:

Price feeds: External data sources that tell the blockchain what an asset is “worth.” If the feed is inaccurate, delayed, or manipulated, the token’s price can misbehave, thus creating a “dependency” risk.

Wrappers: Legal or technical structures that hold the underlying asset and issue a tokenized claim (or “receipt”) in its place. The token’s value depends on the wrapper holding up, thus introducing counterparty or protocol risk.

Smart-contract mechanics: Automated coding rules that control a token’s issuance, transfers, and settlement. These can fail under stress and compromise the asset.

Protocol risk: Exposure to the ongoing solvency, governance, and technical integrity of the platform maintaining the token.

Redemption constraints: Limits on when, how, or whether the token can be exchanged for the underlying asset or cash.

Governance discretion: the ability of token holders, developers, or issuers to change rules mid-flight through votes or admin controls.

Therefore, even when the underlying asset is stable, the tokenized layer adds friction in a way that prevents cash equivalent treatment.

Why the Cash Test Breaks

They have no stable value: Wrapped and synthetic tokens fluctuate based on the underlying asset, protocol design, collateral ratios, liquidity conditions, and market confidence in the wrapper itself.

They are not short-term in nature: Most tokenized assets have no fixed settlement date. Redemption, if it exists at all, is conditional, delayed, or discretionary.

They are not readily convertible: The token’s conversion to cash often depends on counterparties, smart contracts, or secondary markets that can gap, freeze, or disappear.

Using the Basquiat analogy: A tokenized asset is like owning a Basquiat that has been fractionalized, wrapped, and traded via receipts. You may own a share of the painting, hold a claim on a claim, or possess a token that tracks its value. But you can’t walk into a bank and exchange it for cash next week with certainty.

Practical conclusion: The risks outlined are structural, not incidental. Tokenized assets therefore do not meet the definition of cash equivalents not because they lack value, but because their value is mediated, conditional, and structurally volatile.

2. Are Tokenized Assets Financial Assets? (GAAP vs IFRS)

GAAP: Mostly No

A financial asset under GAAP requires:

a contractual/enforceable right to cash, equity or another financial instrument, or

an identifiable issuer obligated to deliver that value.

Tokenized assets usually fail this test. Even when the underlying asset is tangible or financial:

Wrapped tokens depend on custodial arrangements or smart contracts, both of which are not guaranteed by a legal issuer.

Synthetic tokens track asset prices algorithmically, but there’s no enforceable claim to the underlying.

Governance tokens convey power, not cash rights.

NFTs represent unique assets or rights, but typically not redeemable for cash.

In other words, holders hold a representation of ownership or claims, not the underlying rights themselves. Furthermore, GAAP is quite strict in that if they see no enforceable counterparty, the financial asset classification falters immediately.

IFRS: Conditional / More Flexible

IFRS asks: does the token give you contractual or enforceable rights?

Some tokenized assets referencing actual cash-flow rights or legally enforceable claims could qualify.

Example: A token representing a fractional interest in a revenue-generating property, issued under a legally enforceable contract.Most wrapped, synthetic, governance tokens, and NFTs still fail, as these rights are probabilistic, conditional, or non-cash.

Basquiat Analogy: Owning a fractionalized Basquiat receipt doesn’t entitle you to a guaranteed payout or enforceable dividend. IFRS may peek at contracts behind the token, but without a firm claim → it’s still art, not cash.

Practical takeaway:

Under GAAP: Almost all tokenized assets are not financial assets.

Under IFRS: Only tokens tied to enforceable cash-flow claims might be recognized as financial assets; the majority remain off the financial asset spectrum.

3. Can Tokenized Assets Be Inventory?

General Rule: Usually no

Inventory implies assets held for sale in the ordinary course of business. Most tokenized assets are not “for sale” in that sense. They’re representations of underlying assets or rights, held for investment, protocol participation, or strategic purposes.

NFTs? They’re often collectibles or rights, not liquid merchandise.

Wrapped tokens or synthetic tokens? Typically used to represent or access underlying assets, not for routine resale.

Governance tokens? These confer voting/control rights in a protocol or DAO, not cash flow-rights.

When Inventory Treatment Can Apply

Inventory classification is rare but possible for tokenized assets held by firms engaged in active trading operations:

A platform or brokerage might trade wrapped or synthetic tokens frequently.

NFTs may qualify if a firm routinely flips digital art for profit.

Tokenized real estate or equity tokens might be inventory if bought/sold as part of a trading business rather than for long-term holding.

Basquiat Analogy: If you own a fractionalized Basquiat receipt, you’re an investor, a fractional owner, or a participant in the ecosystem. You cannot be treated as a gallery holding a Basquiat to resell in the coming weeks or months. Inventory rules only kick in if your business is actively flipping these “receipts on the canvas” as a core operation.

Practical Implication: For most holders, tokenized assets do not meet inventory criteria. Only specialized trading businesses with consistent buy-sell activity can justify inventory classification.

4. Do Tokenized Assets Default to Intangible Assets?

Under both GAAP and IFRS, an intangible asset is a non-physical asset that is identifiable and controlled by the entity, and from which future economic benefits are expected. Tokenized assets usually meet this definition, not because of what they promise, but because of what they lack.

1. No physical substance: The token is a digital representation, not the underlying asset itself. Accounting looks at what you control, not what the token points to. If what you control is non-physical → intangible.

2. No contractual right to cash: Except in rare cases (legally enforceable revenue rights), the token does not entitle holders to predictable payments. It’s worth noting here that the lack of cash rights does not mean lack of value. It simply means the value is residual, market-driven, or rights-based, which is exactly how intangible assets behave.

3. No defined maturity or settlement date: Most tokenized assets do not expire, settle, or convert on a fixed date. Their usefulness persists as long as the protocol, contract, or ecosystem remains active. That makes them indefinite-lived intangibles, not time-bound receivables or contracts.

Exploring nuance by token type:

NFTs: Unique, non-fungible claims that are intangible by design.

Wrapped and synthetic tokens: These represent underlying assets, but are still intangible because the claim is typically mediated through contracts or protocols.

Governance tokens: Control or voting rights have value, but no physical or cash-backed substance → intangible.

Basquiat Analogy: Think of a Basquiat you own fractionally through a receipt or digital certificate. It is intangible, because even if market participants assign it huge worth, you don’t own the physical Basquiat hanging in a vault. You merely own a recognized, transferable claim of value tied to it. Accounting doesn’t care that the paint exists somewhere. It cares that your asset is:

1. Identifiable (the token is distinct and separable),

2. Non-physical (a digital right or representation),

3. Controlled (you can transfer, sell, or restrict it),

4. Expected to generate economic benefits (through resale, access, influence, or utility).

Practical takeaway: Most tokenized assets default to intangible classification, as this treatment consistently reflects their economic substance: the holder controls the digital representation, not the underlying asset itself.

5. ASU 2023-08: What Actually Changes for Tokenized Assets

ASU 2023-08 moves qualifying crypto assets from cost-less-impairment to fair value through earnings. It is worth noting that this standard does not change the classification. It simply modernizes the measurement of digital format assets. However, many tokenized assets don’t qualify.

To be in scope, the asset must be:

intangible,

cryptographically secured,

fungible,

recorded on a distributed ledger,

not issued by the reporting entity, and

not provide enforceable rights to goods, services, or assets.

This is where tokenized assets split:

Where ASU 2023-08 Does Apply

Some tokenized assets (particularly purely representational tokens) may qualify:

Certain fungible wrapped or synthetic tokens that do not grant enforceable redemption rights.

Tokens whose value is market-based but legally non-redeemable.

Consequently:

Balance sheets improve: Values reflect observable market prices rather than historical cost or one-way impairments. This promotes more transparency in financial statements, especially for volatile holdings.

Earnings volatility increases: Gains and losses from market fluctuations run through earnings each period, directly impacting net income. This makes the P&L much noisier.

Where It Does Not Apply

Many tokenized assets fall out of scope because they do provide enforceable rights:

Tokenized real estate or equity interests with contractual claims.

NFTs granting access, services, or ownership rights.

Tokens backed by custodial or legal redemption arrangements.

These revert to legacy GAAP treatment based on their classification (often indefinite-lived intangibles or other applicable models).

Basquiat analogy: If the token is just the market perception of a Basquiat (i.e., its cultural value, its buzz), it gets marked to market per ASU.

However, if the token gives you legal access to the painting, exhibition rights, or resale proceeds (per bullet point 6 in the conditions listed above), ASU steps back. In this scenario, the accounting treatment is no longer to price the market perception (i.e., the artworld narrative or “buzz”) but to account for the legally enforceable rights and obligations attached to the token, as would be the case in the treatment of similar financial assets.

Bottom line:

ASU 2023-08 helps where tokens behave like market-traded representations only.

It stops short where tokens behave like structured financial claims.

ASU 2023-08 does not standardize tokenized asset accounting. It simply creates a measurement upgrade for a narrow slice of the ecosystem.

6. The Interpretive Gaps Accounting Hasn’t Closed Yet

In my mind, tokenized assets expose a quiet truth, which is that the technology settled faster than the law. The accounting standards gesture at answers, but several core questions remain unresolved.

Legal Enforceability: On-Chain Certainty vs Off-Chain Reality

Most blockchains settle the question of ownership with mathematical finality and precision. However, as we’ve seen in numerous cases, most courts do not. Court decisions involve nuance, judgement and lengthy deliberations. A token may transfer instantly on-chain, but the legal enforceability of the underlying right still depends on off-chain contracts, custodians, and legal frameworks. If a dispute arises, courts adjudicate the contract, not the smart contract. This creates a gap between technical ownership and legal ownership that accounting standards currently assume away.

Jurisdiction: Which Law Governs the Asset?

Tokenized assets often float across borders, but law does not. Some key questions to ask include the following: Is the governing jurisdiction where:

The issuer is incorporated?

Where the asset is located?

Where the holder resides?

Or where the blockchain validator sits?

This matters deeply for classification, recognition, and risk disclosure, yet financial statements rarely reflect jurisdictional ambiguity, even though enforceability may change entirely depending on the forum.

Fractionalization: When Ownership Stops Meaning Control

I acknowledge that fractional tokens promise democratization, but fractional ownership is not the same as fractional rights. Some questions that come to mind for me are: Do token holders have voting power? Sale approval rights? Access to proceeds? Or are they simply exposed to price movements? In many structures, economic exposure exists without legal control, blurring the line between ownership, participation, and speculation. Accounting guidance has not fully caught up to this decoupling.

Blockchain Settlement vs Real-World Registries

A token transfer may be final on Ethereum, but meaningless at the land registry, share register, or IP office. Until off-chain registries formally recognize blockchain settlement as legally authoritative, dual systems of record will persist. That divergence introduces reconciliation risk, legal uncertainty, and a subtle but material question: Which ledger is the source of truth for financial reporting?

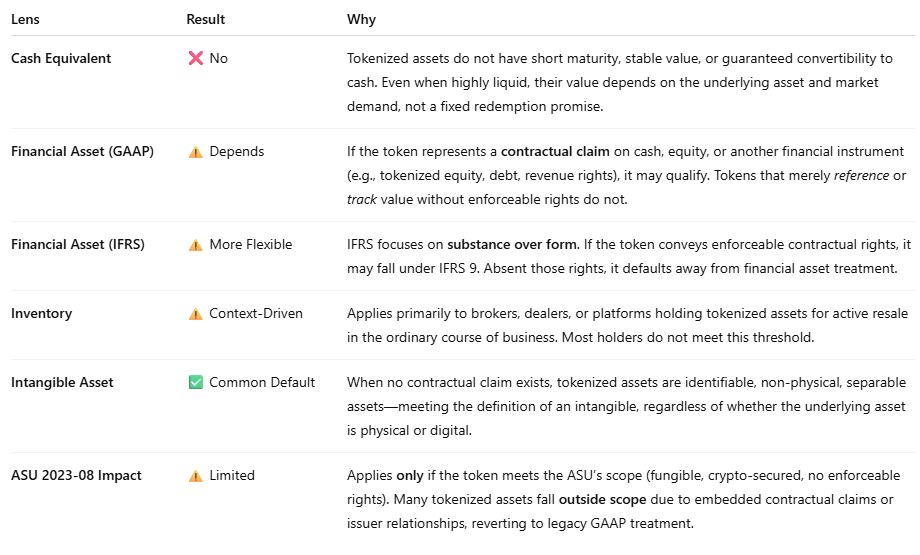

7. Quick Reference Summary Table

Closing

Tokenized assets combine digital innovation with traditional legal and accounting complexity. Their treatment therefore depends less on what the token looks like and more on what legal and economic rights actually transfer to the holder. Finance teams can provide a defensible view of tokenized assets even in the absence of fully settled standards, by framing their approach around four targeted pillars:

Legal Enforceability: Independently assess whether ownership or revenue rights are legally recognized off-chain. Concurrently, audit smart contracts where possible and maintain documentation of how tokenized claims align with enforceable agreements.

Jurisdiction: Here it’s important to identify which legal system governs the underlying asset or rights. Consider jurisdictional risk in valuation, classification, and disclosure policies. Policy choices should subsequently be documented to reflect any uncertainty in cross-border enforcement.

Fractionalization: Track the difference between fractional ownership and practical control. Policies should clarify whether token holders have voting rights, access to proceeds, or only economic exposure, and disclosures should reflect this distinction.

Blockchain Settlement vs Real-World Registries: Reconcile on-chain transactions with off-chain records (e.g., land, equity, or IP registries). Establish internal controls to address gaps between blockchain settlement and legal recognition of the underlying asset.

As with most digital assets, maintaining audit-ready records, clear internal policies, and robust disclosure practices is key. In art speak, the Basquiat may be digital, but ownership questions remain very real. By properly documenting assumptions, judgments, rights, control, and legal recognition, you ensure your accounting and audit stance respects both the art and the ledger.

Disclaimer: The content in this newsletter is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute individualized legal, financial, tax, accounting, or investment advice. Although I am a qualified professional, the analysis provided is not tailored to any specific entity or situation. No warranty is made as to the accuracy or completeness of the information, and no liability is accepted for actions taken based on it.