Rat Poison or Real Infrastructure?

Putting Digital Assets Under the Microscope

I’ve been researching blockchain and digital assets for quite some time now. Along the way, I’ve read the work of many of the ecosystem’s most visible thinkers: Anthony Scaramucci’s The Little Book of Bitcoin, Chris Dixon’s Read Write Own, Vitalik Buterin’s essays on coordination and credible neutrality, and more recent macro-oriented analyses from writers like Lyn Alden and Nic Carter. I’ve studied how blockchains actually function, how decentralization is engineered, how incentives are encoded, and how governance migrates from institutions into protocols. Certain words surface again and again in this literature: decentralized, autonomous, permissionless. The benefits, proponents argue, are almost self-evident. Anyone can participate. Intermediaries are removed. Capital moves freely. Even the underserved (i.e., the unbanked, the excluded, and the overlooked) can finally access financial infrastructure on equal terms. It’s a compelling story.

But I am a Chartered Accountant. And every accountant, at some point in their career, is taught a principle that quietly governs everything we do: professional skepticism. Doubt is not cynicism. It’s protection. We are trained to question narratives, interrogate assumptions, and separate what appears valuable from what is valuable.

I bring that same lens to digital assets. Not because I reject the technology, but because I take it seriously. Over the past few months, I’ve researched and written a series classifying the five major categories of digital assets — native tokens, stablecoins, tokenized assets, utility and governance tokens, and DeFi positions — using traditional accounting logic (Have a read of this and this). The exercise surfaced something uncomfortable but important: many digital assets are economically expressive, yet structurally thin. They trade. They fluctuate. They attract capital. But they often lack what accounting has always demanded before capital formation becomes durable: economic substance.

This article is not about defending digital assets against its critics. In fact, many of the critics — including Warren Buffett — are right in ways the industry is reluctant to admit. Volatility is real, speculation is rampant and much of what trades today deserves skepticism. The better question is: can accounting and economic logic help us design a different kind of digital asset product; one with clearer substance, more durable value, and less dependence on hype?

That is the aim of this piece.

To move beyond slogans and into structure.

To ground digital assets in history, accounting, and intellectual economic reasoning.

And to seriously interrogate what kind of crypto market would persuade even the most disciplined capital allocators that something investable is being built here at all.

Part 1: What the Naysayers Are Actually Saying

Spend enough time around institutional investors, macroeconomists, or even at corporate speakeasy invites, and the skepticism begins to sound less like hostility and more like fatigue: “How can this ever work as a currency?” That’s usually the first question. Once a U.S. or China-backed stablecoin gains global acceptance, many argue, Bitcoin will resemble less a monetary future and more a redundant, historical experiment. Others push back more thoughtfully. Bitcoin, they say, was never meant to be a currency in the everyday sense. Its real product–market fit is closer to a sovereign monetary asset or digital store of value.

President Trump will appear to agree having signed on March 6, 2025 an executive order that marked the “Establishment of the Strategic Bitcoin Reserve and U.S. Digital Asset Stockpile.” The US in its capacity as the largest known state holder of bitcoin in the world (~198K BTC circa as of Aug. 2025), intends to capitalize the reserve with bitcoin already owned by the federal government.

Separately, the digital asset stockpile constitutes non-bitcoin assets. This ofcourse is in line with the President’s vision to oversee the United State’s ascent to “the crypto capital of the world.”

I’d also recommend this video analysis:

Through this lens, it starts to resemble gold more than cash. If your instinct is to reject that framing outright, Bitcoin proponents will gently suggest you read The Bitcoin Standard or Lyn Alden’s Broken Money before dismissing it entirely.

Political Argument

Then there’s the political irony which I think is almost too neat to ignore. Crypto markets had already begun a powerful recovery from the 2022 crypto winter, with Bitcoin climbing from roughly 16–20k at the start of 2023 to above 40k by year‑end, returning more than 150% as part of a broader macro and ETF‑driven rally.

In 2024, total crypto market capitalization nearly doubled again propelled by factors such as spot Bitcoin ETFs, shifting interest‑rate expectations, and expanding institutional participation. Against that backdrop, Donald Trump openly courted the crypto vote, actively seeking the industry’s donations and support with a high‑profile speech at the Bitcoin 2024 conference and outreach to major mining and exchange executives. Analysts credit his reelection and pro‑crypto rhetoric with adding a noticeable “Trump bump” in late‑cycle price action, particularly in Q4 2024 that saw Bitcoin set a new all‑time high above 100k in December. In the aftermath, markets rallied and traders made billions. On the surface, it looked like a triumph. Until the aftertaste set in: political pumps do not create durable price floors, they create cliffs, and markets are now discovering just how little structural support exists underneath the charts once the narrative exhausts itself.

Some critics are even less charitable. They see crypto as a pyramid scheme wherein its value is sustained by convincing the next buyer to show up (See Warren Buffet’s critique in Part 2 below).

Gold, they argue, is tangible. The dollar is backed by a state. Crypto is backed by belief. When belief falters, what’s left?

Infrastructure Argument

This leads to a deeper, more uncomfortable question: What would it take for Bitcoin to have a stable benchmark? And how, if at all, could Bitcoin evolve beyond narrative-driven volatility into something that behaves like a durable store of value over a medium to long-term horizon?

Others widen the lens even further. Do not confuse technology with its first-generation applications, they warn. AI and blockchain are transformative, yes, but early products are often flawed. OpenAI’s compute economics are fragile just like Bitcoin’s “digital gold” narrative is increasingly challenged by scalability constraints and theoretical quantum vulnerabilities. The real bubble, they argue, isn’t crypto or AI; it’s the assumption that the first popular implementations are the final form.

Psychological Argument

By late 2025, something else had shifted: market psychology. People stopped asking how high can this go? and started asking show me the money. What does it actually do? What productive output does it enable? How does this create value outside the trading loop? Some critics go further, arguing that crypto speculation has absorbed vast amounts of human capital into unproductive activities. A close friend of mine offered a sharp take, suggesting that speculators be “severely punished” by markets, so that they’re forced back into real jobs. Harsh, but revealing.

Others point out the knowledge gap. Survey a thousand people in any major city. Fewer than ten can concretely explain how crypto works. Hundreds have bought it anyway. How can something so poorly understood be worth trillions? The counter, of course, is obvious. Banks and institutions have been using blockchain technology quietly for years. Lack of public understanding doesn’t equate to lack of value. The problem isn’t the technology; it’s that the coins and tokens layered on top of it are often speculative, fragile, and poorly structured.

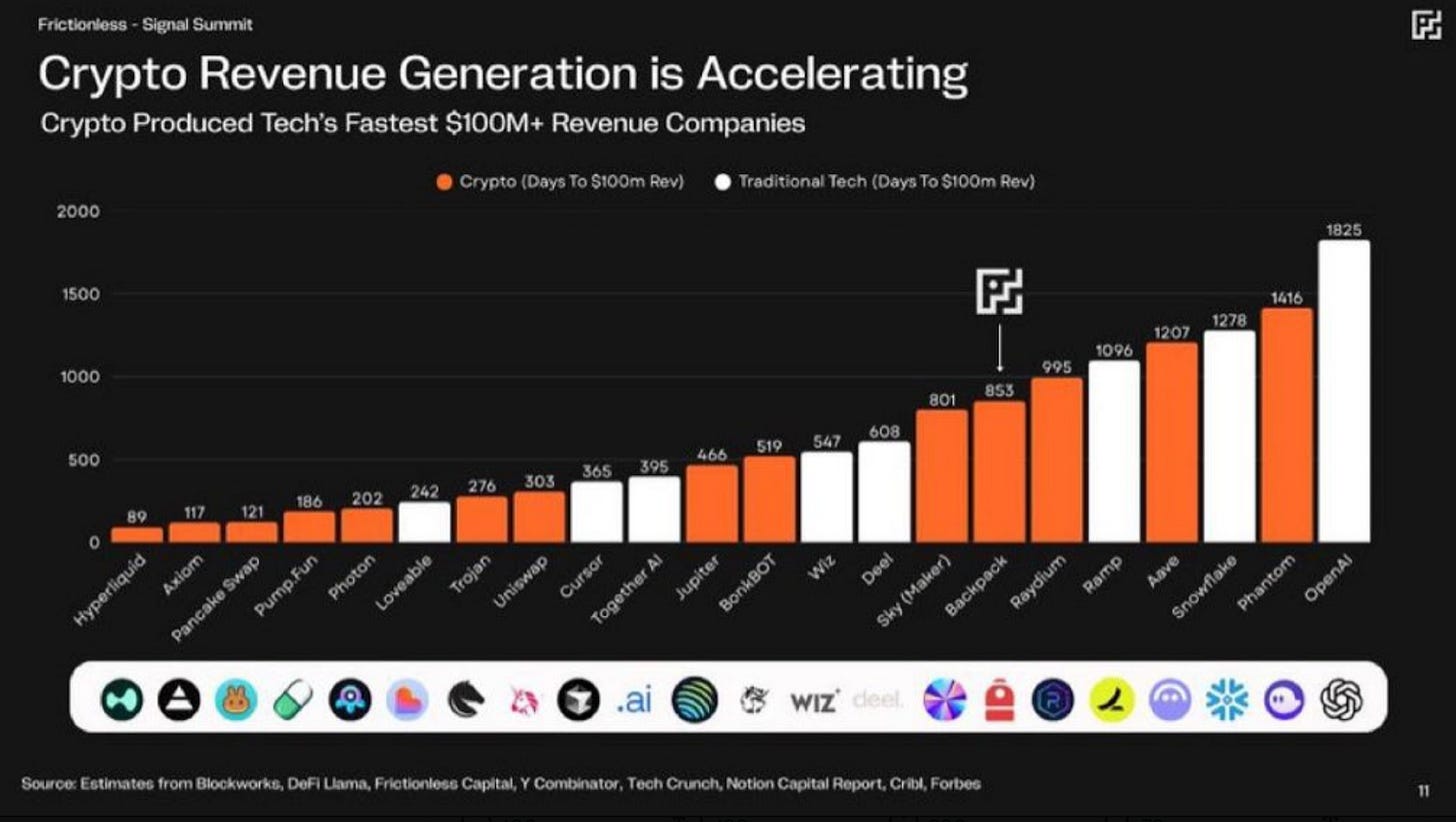

And so the core criticism repeats itself in different forms: Crypto is valueless, unknowable, and too volatile to analyze. One month it’s $160,000. The next it’s $80,000. What fundamental analysis could possibly justify that? Yes, crypto companies are among the fastest ever to reach $100 million in revenue. As one social media user dryly noted: they’re also some of the fastest to reach zero.

This article doesn’t dismiss these critiques. It takes them seriously. Because buried inside the skepticism is a legitimate challenge that accountants are trained to recognize instinctively:

Part 2: Before the Accounting, Step Back

Before we get anywhere near balance sheets or valuation models, it’s worth doing something investors are often reluctant to do in the middle of volatile markets: step back. One of the most useful books I’ve read in this regard is Andrew Ross Sorkin’s 1929. It’s not just a history of Wall Street’s eponymous stock market crash; it’s an electrifying study of psychology, of how optimism and speculative cycles harden into certainty, how narratives crowd out caution, and how financial systems repeatedly confuse future promise with present value. The patterns are uncomfortably familiar: leverage arrives before cash flows, belief outruns fundamentals, and markets price in a future that hasn’t yet materialized. That framing matters!

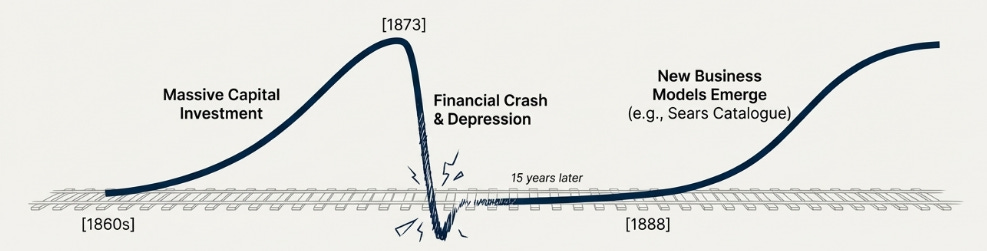

Economist Noah Smith offers a helpful lens here, through what he calls the Railroad Scenario, and it maps eerily well onto today’s digital asset markets.

In the mid-1800s, railroads were not a speculative novelty. They were genuinely transformative. In fact, the railroad buildout was, in percentage terms, the single largest capital expenditure boom in U.S. history; far larger than today’s AI data center investments. And yet, in 1873, a wave of railroad-related loan defaults triggered a banking crisis and a decade-long depression.

Here’s the crucial point: the bust didn’t happen because America built too many railroads. The miles of track never stopped increasing. What failed was the financing timeline. Railroads were funded faster than they could capture economic value. There is no limit to how quickly financial systems can deploy capital. But there is a limit to how fast real economic value can be created. Railroads needed time; time for cities to emerge, industries to reorganize, and entirely new business models to form. The Sears catalog, which revolutionized retail by leveraging rail distribution, didn’t even appear until 1888; fifteen years after the crash. The lesson is subtle but devastating: transformative technologies can be economically correct and financially premature at the same time. Even if blockchains, decentralized finance, and tokenized systems eventually deliver the value their proponents claim, markets may have capitalized that future far too early and far too aggressively.

Which brings us neatly to Warren Buffett.

Buffett, Bubbles, and Behavioral Caution

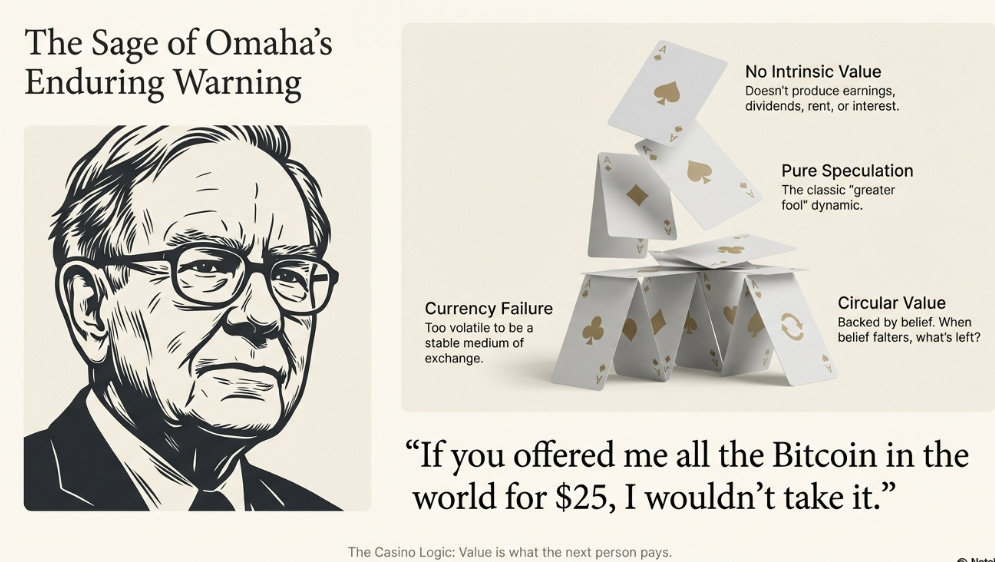

I’ve long been a student of Warren Buffett’s shareholder letters and investing philosophy, wherein he only buys shares in companies with strong fundamentals, predictable earnings, and long-term competitive advantages. His thinking is disciplined, historically grounded, and above all, allergic to speculation masquerading as investment. The majority of digital assets don’t fit within his framework of rational, long term investments and accordingly, he is unapologetically hostile to the ecosystem.

Buffett’s tone is often labelled crude and dismissive — “rat poison squared” — but that misses the point. His language is intentionally blunt because his objective is behavioral caution. He wants the public to avoid financial instruments he believes are structurally incapable of delivering long-term value. To Buffett, these “assets” fit neatly into a familiar historical pattern.

It echoes Tulip Mania in the 17th century. Assets traded feverishly not for their utility, but for the belief that someone else would pay more tomorrow.

It resembles the dot-com boom, where technological promise was real, but valuations assumed profitability long before it arrived.

And it rhymes with the subprime mortgage crisis, where financial engineering obscured the absence of underlying cash flows.

Buffett’s critique is consistent and philosophically rigid:

First, no intrinsic value: Crypto assets don’t produce earnings, dividends, rent, or interest. They don’t manufacture goods or deliver services. In Buffett’s value-investing framework, assets must generate cash flows. An S&P 500 index fund does. A farm does. A business does. Crypto does not.

Second, pure speculation: In Buffett’s view, the only way to make money in crypto is for someone else to pay more later; the classic “greater fool” dynamic. Price appreciation becomes detached from productivity, and value becomes circular.

Third, currency failure: He doesn’t believe cryptocurrencies function well as money; neither as a stable medium of exchange nor a reliable store of value. After more than a decade, retail adoption remains marginal.

One online user’s quote captures This thinking perfectly:

“Since 2009, 19,646,162 Bitcoins have been mined. So, 93.6% of all possible Bitcoins are in wallets somewhere. Yet, after 15 years, only an infinitesimally small number of retailers accept them as payment. So, if anything, it is just a store of wealth at best. But there are many time-tested ways to store wealth, so what’s the big deal with Bitcoin? … Rarity is no guarantee of value appreciation. What are we left with? Human nature; the something-for-nothing syndrome.”

Finally, volatility: Buffett views extreme price swings as disqualifying. Assets suitable for pensions, insurers, or long-term capital pools must be predictable. Crypto’s boom–bust cycles place it firmly outside that universe.

“If you offered me all the Bitcoin in the world for $25, I wouldn’t take it,” Buffett once said, not as hyperbole, but as philosophy.

And importantly, he’s been consistent. He doesn’t own any cryptocurrencies and never plans to. That alone earns a certain respect.

Part 3: The Market Teaches the Same Lesson Again

By Q3 2025, the debate stopped being theoretical. Markets did what markets always do when leverage meets uncertainty: they snapped. At the surface level, the explanations sounded familiar. Anxiety simply crept into both equities and crypto as investors tried to second-guess the Federal Reserve. Would further rate cuts come sooner? Later? Not at all? However, the mechanics were subtler than headlines suggested. Yes, the Federal Reserve reduced rates. But markets don’t trade on actions alone; they trade on expectations relative to positioning. Around this period (i.e., Q3 2025), risk assets had already priced in an optimistic path: multiple cuts, rapid easing, and a soft landing that would justify elevated valuations across tech, AI, and digital assets, including crypto. When the Fed finally moved, the cut landed not as fresh stimulus, but as confirmation that growth was slowing faster than many had assumed.

Quantitative easing is an unconventional monetary policy where a central bank electronically creates money to buy large amounts of financial assets, to inject cash into the economy, lower long-term interest rates, and stimulate borrowing, spending, and investment during economic downturns. Ultimately, the aim is to boost economic growth and hit inflation targets.

Effect of The Rate Cuts

The rate cut didn’t signal relief, it signaled concern. For institutional investors, that distinction matters. Lower rates reduce the risk-free return, but they also compress forward growth assumptions. When easing is interpreted as defensive (aka: “bearish”) rather than expansionary (aka: “bullish”), capital rotates out of speculative assets and back toward liquidity, duration management, and balance-sheet resilience. This pressure was felt almost immediately. Digital assets behave less like currencies and more like long-duration risk assets; similar to high-growth tech stocks whose value is anchored in distant, uncertain future payoffs. When the macro narrative shifts from “growth acceleration” to “damage control,” those assets are repriced aggressively. At the same time, doubts were mounting about the AI boom itself. Data centers, hyperscalers, and compute-intensive models were consuming capital at eye-watering unprecedented rates, but durable cash flows lagged behind the hype. As questions emerged about who would ultimately pay for this infrastructure and on what timeline, institutions began reducing exposure to the most speculative corners of the market, and the national speculative appetite quickly evaporated.

The result was an immediate wave of selective recalibration.

The Winter of Discontent

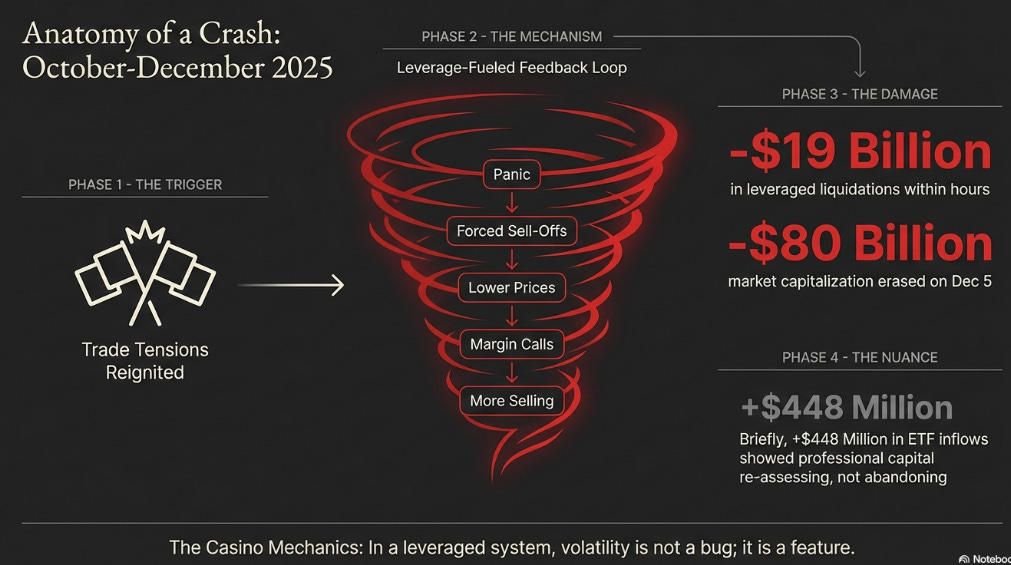

On October 10, a flash crash tore through the market. When President Donald Trump reignited trade tensions with China, panic rippled across global assets. In cryptocurrency trading, where leverage is not an exception but a design feature, that panic immediately triggered automatic liquidations at scale. Within hours, roughly $19 billion was erased through forced sell‑offs, and margin calls began to cascade. As prices fell, investors were compelled to sell simply to meet collateral requirements, pushing prices lower still, a reflexive feedback loop Buffett has warned about for decades: Volatility not as abstraction but as mechanics.

Yet the story isn’t one of uniform collapse. In late October 2025, spot Bitcoin and Ethereum ETFs recorded a combined $448 million in net inflows, with Bitcoin funds adding roughly $202 million over several sessions and Ethereum ETFs attracting about $246 million, reversing prior outflows and signaling renewed institutional demand.

However, the downturn swiftly re-emerged. In mid-November 2025, after a wave of inflows earlier in the year, U.S. spot Bitcoin ETFs saw significant net outflows—including multi-billion-dollar withdrawals—signaling a pullback in institutional conviction. Outflows from regulated flagship funds like BlackRock’s iShares Bitcoin Trust (IBIT) revealed that even the long-horizon allocators were reducing risk and rebalancing exposures. Notably on December 5 2025, the broader crypto market shed $80 billion in capitalization in a matter of hours, dragging total market value down to roughly $3.1 trillion.

Seen through Buffett’s lens, none of this is surprising. This wasn’t retail fear but professional capital doing what it always does in markets without intrinsic floors: stepping back as volatility rises and macro clarity fades. In highly leveraged environments, assets without cash flows lack stabilizers when sentiment turns, leaving belief—fragile under stress—as the only support. This is precisely why Buffett distrusts volatility dressed up as innovation. But this moment forces a deeper question:

If crypto markets keep breaking in predictable ways, is that an indictment of the technology itself or of the financial structures we’ve chosen to build on top of it?

Part 4: Where Buffett Is Right and Where the Picture Is Incomplete

Buffett’s critique is devastating if crypto is judged as a finished investment product. The open question this article turns toward is whether it must remain that way or whether any enduring value lies not in momentum, but in economic substance shaped by better design. At present, his critique lands squarely on tokens as investments, not on digital assets as financial infrastructure. Conflating the two obscures what is actually happening in crypto markets, and why the same volatility keeps reappearing. In practice, crypto is not one market. It is two markets operating simultaneously and often uncomfortably so.

First, there is speculation; the casino. This is where Buffett’s instincts are at their sharpest.

Second, there is infrastructure; the computer. This layer does real work, even if it is frequently mispriced, misunderstood, or overshadowed by hype.

Chris Dixon captures this distinction cleanly: every transformative technology arrives wrapped in speculation. The internet had pets.com and day trading chat rooms, but it also produced TCP/IP and cloud computing. Crypto follows the same pattern. The mistake is assuming the casino is the computer.

Why Speculation Dominates What Most People See

Most retail-visible crypto activity is not infrastructure. It is narrative-driven speculation. Tokens are marketed with sweeping claims (“this replaces banks,” “this is the future of money”), but remain thin on cash flows, weak on governance, and priced largely on momentum. Early insiders enter cheaply, exit first, and leave later buyers exposed. This is not novel. It is the recurring structure of speculative booms.

The parallel to tulip mania, the dot-com bubble, or subprime mortgages is not that crypto is the same asset. It is that complexity masks risk. Retail capital enters late, gains are privatized early and losses are socialized broadly.

It is also why Buffett’s skepticism is rational when applied to trading desks and token hype; the parts of the market most sensitive to leverage, narrative, and reflexivity.

When a Token Exists Mainly to Trade

Buffett’s critique lands hardest where the token price is the product. There are reliable red flags:

Utility is vague, deferred, or perpetually “coming soon.”

Revenues do not accrue to token holders.

Governance exists largely on paper.

Incentives rely on “numbers going up.”

Cash flows are circular, internal, or purely reflexive.

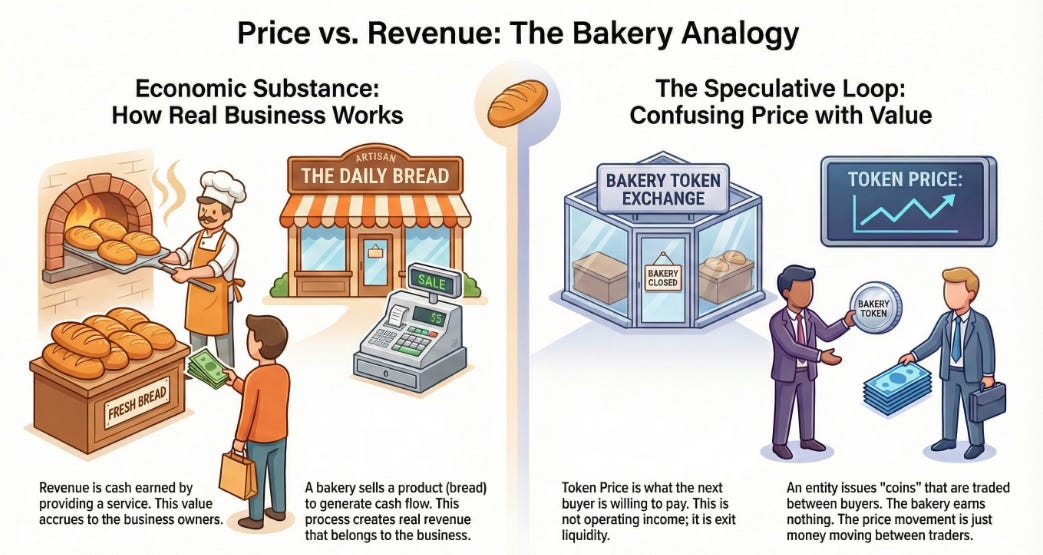

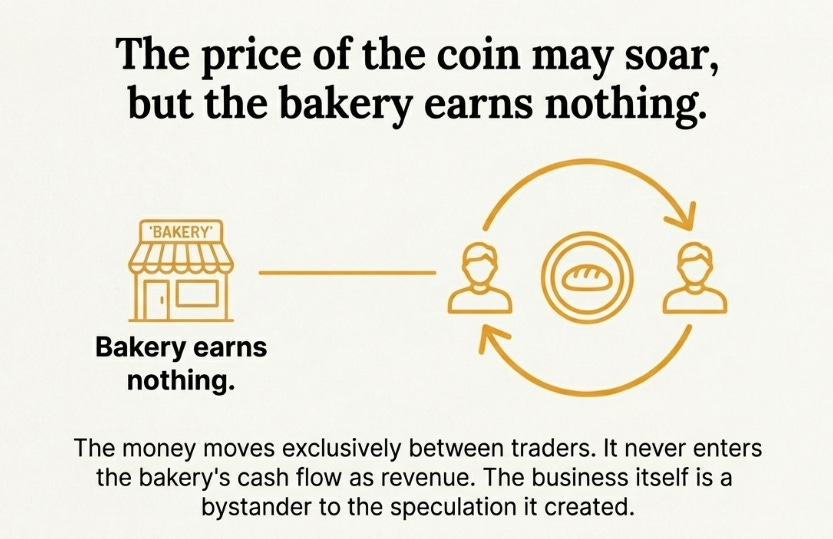

Meme coins, many governance tokens, and yield products with self-referential economics fall squarely into this category. The underlying issue is simple but often obscured: PRICE IS NOT REVENUE!

Revenue is cash earned by providing a service; this may include fees, interest, settlement, custody. Token price is merely what the next buyer is willing to pay for the token. When people say revenue does not accrue to token holders, they mean the trading platform may earn real money, but token holders have no claim on it. No dividends, no buybacks, and no enforceable profit participation.

Selling a token is therefore not operating income. It is exit liquidity. This is Buffett’s red flag.

A useful analogy is a bakery. The bakery earns revenue by selling bread. That money belongs to the owner or shareholders. Now imagine the bakery issues “Bakery Coins” that customers trade among themselves. When one customer sells a coin to another, the bakery earns nothing. Money is simply moved between customers, but no bread is sold and no value is created.

Buffett trusts the bakery. He distrusts the coin. Early holders of the coin are not investing in the bakery’s production; they are exiting into cash. Late buyers inherit the risk. If demand stalls, the mechanism collapses and the bakery coin becomes worthless. That is speculation, not ownership. The pdf trail below depicts how this mechanism functions.

Why Certain Crypto Products Stack Risk

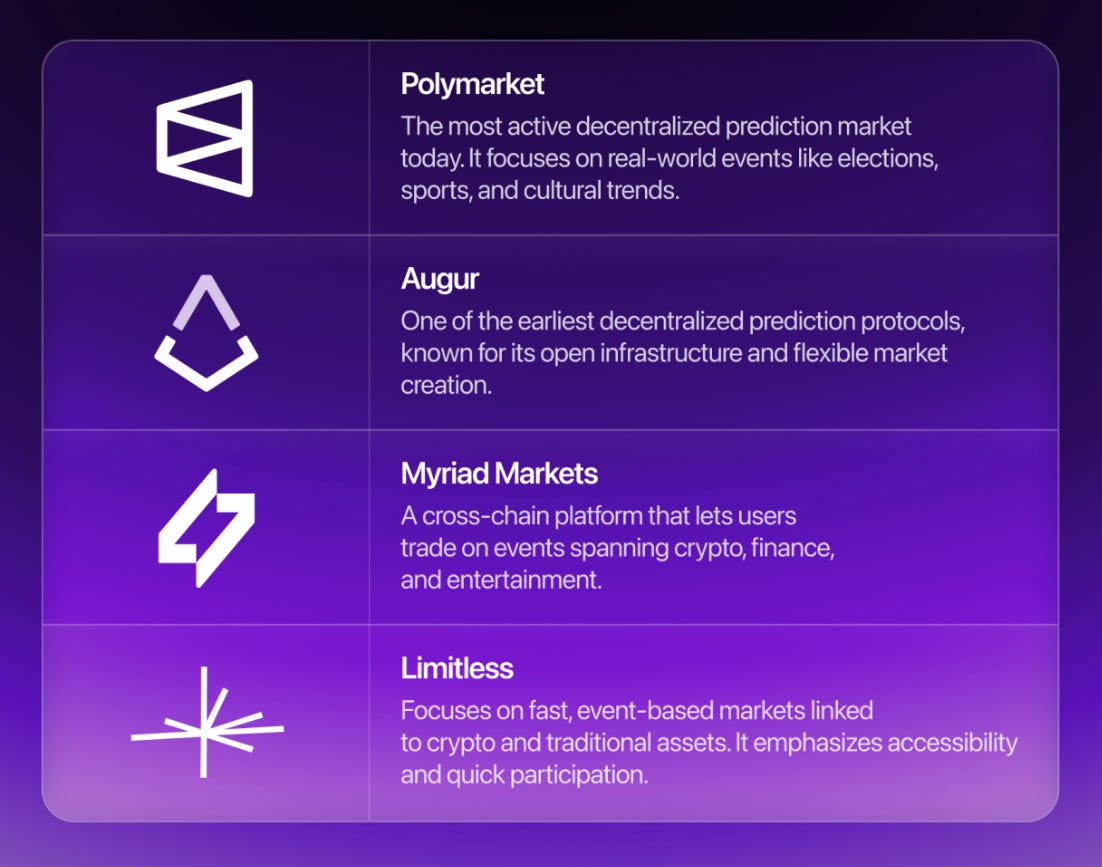

This distinction becomes clearest in hybrid products like token-based prediction markets. At a high level, prediction markets allow users to buy and sell outcome shares (typically “Yes” or “No” tokens) whose prices reflect the market’s collective probability estimate for a given event. However, when these outcome shares are implemented as freely tradable tokens, two distinct risks can compound:

Forecast risk: being wrong about the underlying event outcome, and

Market structure risk: exposure to token price volatility, and exit timing prior to settlement.

While an outcome token may settle to a fixed payoff if held to resolution, it does not represent ownership of a productive asset or a claim on recurring cash flows. Its interim value prior to settlement is driven by tradeability, market sentiment, liquidity conditions, and timing rather than by asset-level performance. Yes, the payoff is discrete and terminal BUT the interim economics is purely transactional.

This is precisely the type of structure Buffett would avoid: instruments with no intrinsic yield, no reinvestment capacity, and no compounding engine, only the expectation that someone else will pay more or less for the same probabilistic claim before it expires. As information infrastructure, prediction markets can be highly efficient but as investment assets, they fail most investment-grade tests.

But the Casino Is Not the Whole System

Stopping here, however, would miss the other half of the picture. Not all crypto exists to be traded. Some of it exists to move, settle, record, and control value.

This is the computer.

Just as the internet separated speculative dot-com stocks from core infrastructure like TCP/IP and cloud services, crypto separates meme coins from financial rails, including:

Stablecoin settlement,

Custody systems,

Immutable ledgers,

Smart contracts, and

Tokenization frameworks

These components perform real value-added work. They reduce friction, automate enforcement, and create new ways to represent ownership and obligations.

Take tokenized securities as an example. The token is not the asset; it is the wrapper. The asset itself remains off-chain as a legally recognized financial instrument—whether equity, debt, revenue-sharing interests, or claims on real-world assets like real estate or receivables—while the token digitally represents the rights attached to it. When these structures are poorly specified, tokens drift into speculation, trading on hype rather than underlying economics. When well designed, however, the token functions as infrastructure, not a speculative asset: a programmable ledger entry anchored to assets that already generate cash flows or enforceable rights. The blockchain doesn’t create the value; it simply records ownership more efficiently, automates settlement, and enforces transfer rules.

Why This Matters

As regulatory clarity improves, some digital assets begin to resemble traditional finance, not because the technology changes, but because design choices do. When rights are explicit, cash flows traceable, and controls enforceable, the ecosystem stops looking like a casino chip and starts looking like infrastructure. Buffett’s warning remains essential. But it applies most cleanly to markets built on resale hope rather than real economic claims. The harder question and the one that follows is how to design crypto systems so value creation, not volatility, sits at the center.

The internet’s history is instructive:

The casino: dot-com stocks priced on narrative and traffic rather than cash flows.

The computer: TCP/IP, databases, cloud infrastructure. These are boring and invisible, yet wholly essential.

Crypto follows the same bifurcation:

The casino: meme coins, hype-driven governance tokens, circular yield instruments.

The computer: payments rails, custody systems, settlement layers, ledgers, programmable finance, and tokenized real-world assets.

Only the second category reliably supports auditability, controls, and long-term value creation.

Part 5: Potential Solutions To Uncover Economic Substance

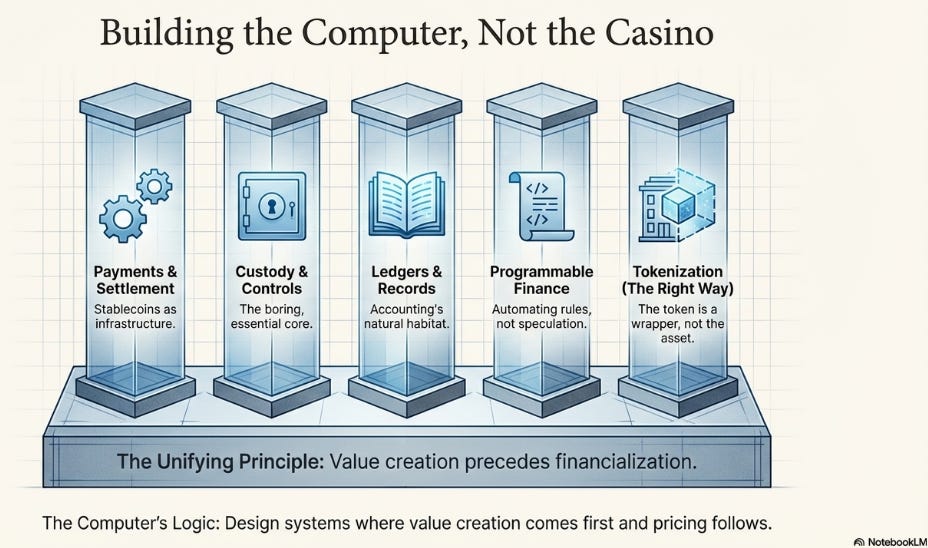

The enduring mistake in crypto debates is treating tokens as the innovation. In my opinion, they are not! They are merely one possible interface. The real opportunity lies in the financial infrastructure beneath them because these are the systems that move value, record rights, enforce rules, and reduce friction. This is where accounting, assurance, regulation and controls become anti-bubble forces. The bottom line is simple but uncomfortable: Avoid places where the token is the business. Seek structures where the token is incidental to an underlying economic function.

Crypto as an Asset Depends on Context

From a traditional value-investing perspective, Buffett is largely right. Most tokens fail the intrinsic value test. But as I outlined earlier, crypto isn’t one thing. It is simultaneously a speculative market (where Buffett’s skepticism is fully justified), and an emerging financial infrastructure layer (where his framework is incomplete).

This distinction matters. Infrastructure is rarely investable early in its lifecycle, but it often becomes indispensable later. Crypto today resembles the internet in the 1990s:

speculation dominated because the technology arrived before the economic models matured. However, the market’s early, noisy, and inefficient nature did not invalidate the rails themselves, as we’ve since come to see. The real question, then, is not “Is crypto an asset class?” but rather “Where does economic substance accumulate over time?”

Where Maturity Truly Emerges: Proven, Focused Opportunities

Rather than proposing speculative moonshots, the credible path forward lies in narrow, disciplined applications where digital assets improve existing financial functions.

Payments and Settlement (Stablecoins as Infrastructure, Not Trade): Stablecoins remain the most demonstrably useful crypto product to date. I don’t view them necessarily as investments, but as settlement technology. They facilitate 24/7 settlements, cross-border payments without correspondent banking friction, and lower transaction costs.

From an accounting lens, stablecoins increasingly resemble cash equivalents not speculative assets. This is why even critics of cryptocurrencies often support digital money in principle while rejecting unbacked, anonymous tokens. The value here accrues to: payment rails, compliance infrastructure, and reconciliation and reporting systems, not to speculative token appreciation.

Custody, Controls, and Key Management (The Boring Core)

If crypto has a hidden Achilles’ heel, it has to be custody. Critical questions here include: Who controls assets? How are keys stored? What happens on loss, death, or fraud? These are not philosophical questions, but balance-sheet questions. Large scale institutional adoption depends on: segregation of duties, recoverability, audit trails, and legal clarity over control versus access.

This is where cryptocurrencies begins to resemble traditional finance again and where accountants, auditors, and regulators become central rather than adversarial. The firms building institutional-grade custody, reporting, and controls are quietly solving the hardest problems in the ecosystem. Yet another example of infrastructure with economic substance.

Ledgers and Record-Keeping (Accounting’s Natural Habitat): Blockchains excel at tamper-resistant record-keeping. For accounting, this matters enormously for ownership verification and immutable audit trails. Used properly, blockchains function less like speculative markets and more like shared sub-ledgers that reduce reconciliation risk and enhance transparency. Not exactly glamorous in my opinion, but really powerful stuff!

Programmable Finance: Smart contracts are most valuable not where they speculate, but where they automate rules such as: escrow, collateral management, margin requirements and settlement conditions. When rules are explicit and enforceable, automation reduces operational risk. When rules are vague or reflexive it magnifies it. Here you can see that the distinction is architectural, not ideological.

Tokenization (When the Token Is Not the Asset): Tokenization is where Buffett’s framework is most often misapplied. However, properly designed tokenization does not create value out of thin air. It digitizes ownership records, streamlines settlement, improves liquidity when appropriate, and preserves legal claims off-chain. Here, the underlying asset remains the source of cash flows and value. The token is merely the wrapper. Missteps occur when the legal enforceability is weak, rights are unclear, liquidity is overstated, and/or secondary markets detach from fundamentals. Well-specified tokenized securities don’t violate Buffett’s logic; poorly governed ones do.

Land As a Critical Frontier: One underexplored opportunity sits at the intersection of crypto infrastructure and the world’s oldest asset: land.

As Mike Bird argues in The Land Trap, land’s immobility and role as collateral make it central to financial systems. Mortgages, leverage cycles, and inequality all orbit land. Digital asset rails could meaningfully improve: land registries, collateral tracking, lien transparency, cross-border ownership records. The aim here isn’t to turn land into meme tokens but to improve how claims, encumbrances, and transfers are recorded and enforced. This is infrastructure, not speculation.

Check out my deep dive on how I’ve proposed constructing the five pathways above into investable, “Buffett-approved” assets.

The Unifying Principle: Economic Substance Over Hype

Economic substance is not a vague concept. It depends on structure, intent and accounting treatment. It reliably emerges where the following conditions are met:

cash flows exist and are identifiable,

rights are legally enforceable off-chain,

incentives align stakeholders with long-term value,

controls are auditable + transparent, and/or

value creation precedes financialization.

This, in my opinion is how immature technologies grow up. Just as Jensen Huang didn’t speculate on AI applications but built the infrastructure that intelligence would come to rely on, the enduring opportunity in the digital asset ecosystem lies not in betting on tokens, but in designing systems where value creation comes first and pricing follows later. And that is how you persuade Buffett (and pesky accountants). Not with hype, but with structure.